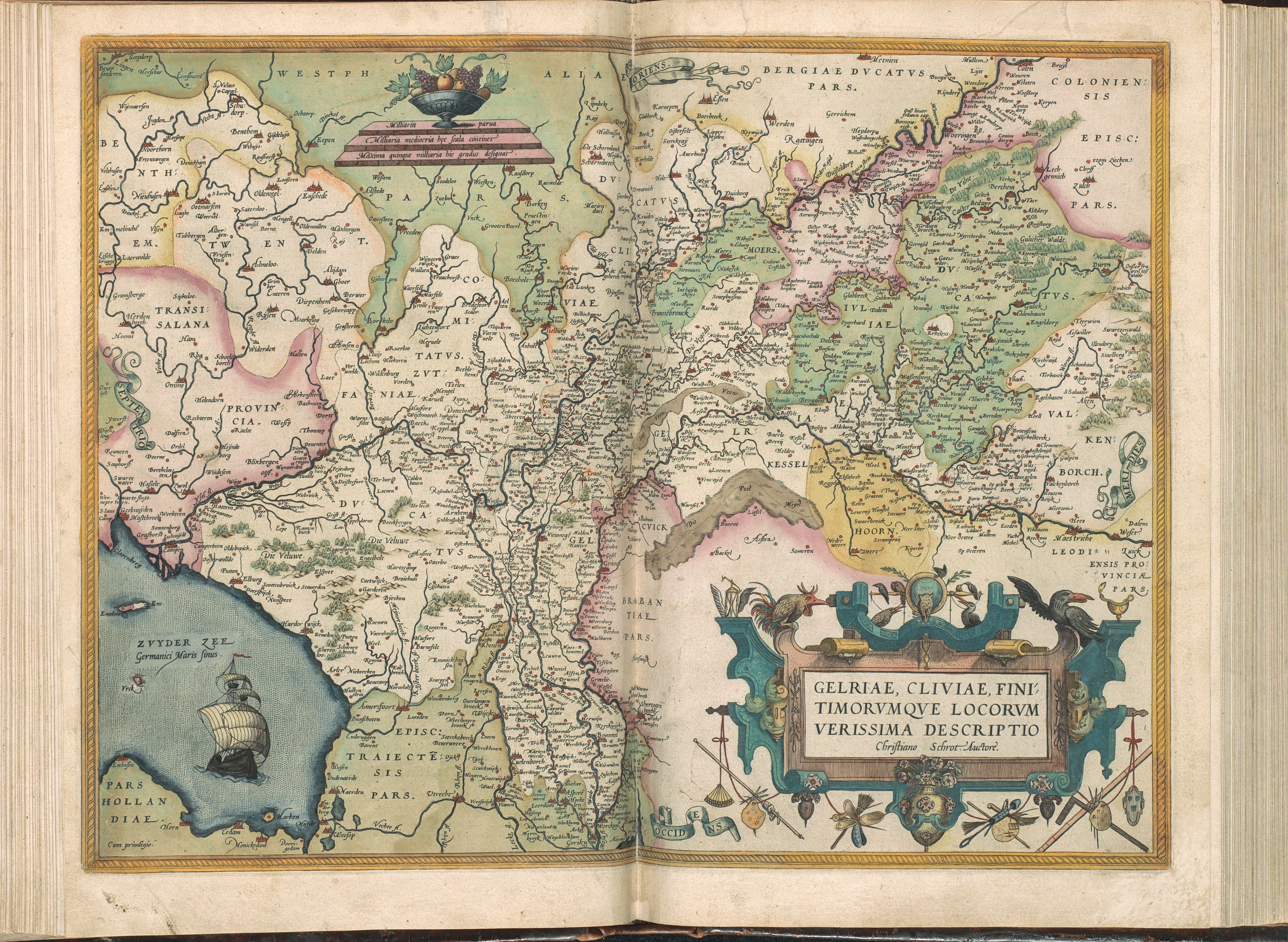

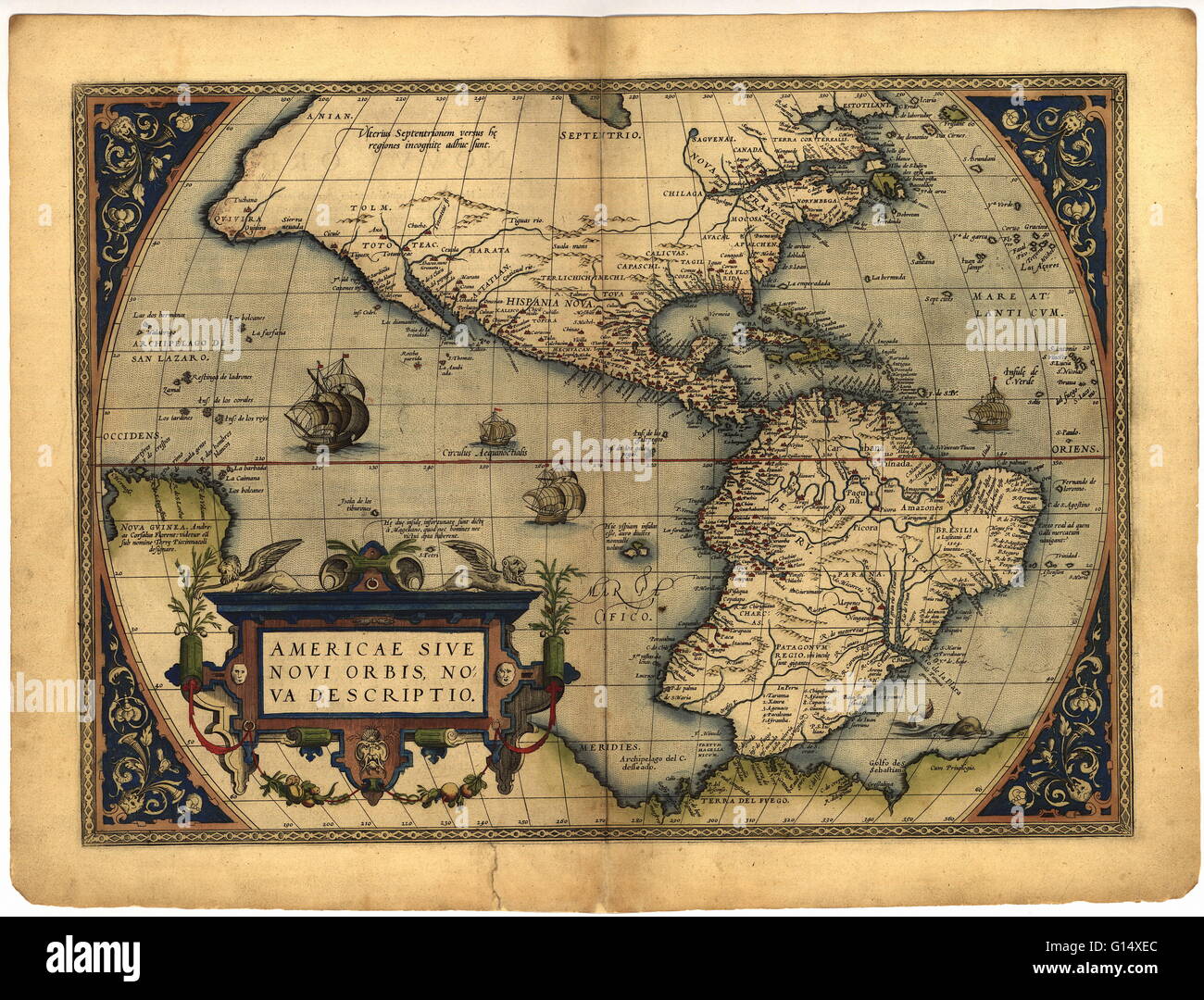

What I find most fascinating about the frontispiece is that, at least in two English editions that we have (16), there is a facing page explanatory verse, “The Meaning of the Frontispice.”Īpparently Hondius didn’t want to count on his readers understanding what they were looking at. It was significantly more successful than the original incarnation, and 29 editions were published between 16. However, in 1604 an Amsterdam cartographer named Jodocus Hondius purchased the copper plates of Mercator’s maps, and supplementing them with additional text and maps, published Mercator’s Atlas in a form much closer to what the man himself must have wished. Mercator’s atlas was published in 15, but it was lacking many major maps (such as Asia, Africa, and even Spain and Portugal!), and was not a particular success. After his death in 1594, Mercator’s son and nephews worked quickly to get his dream published, and they succeeded on a technicality. Mercator spent the final 25 years of his life working on maps for his atlas, but ran out of time. However, unlike Ortelius, Mercator intended to create all of the maps himself. Mercator’s world map of 1569 was an immediate success, but he, like Ortelius, wanted to create an atlas, a single bound volume that could contain more detailed maps of many locations. Mercator, a close friend of Ortelius, is best known today for his projection that is, a methodology for consistently representing a round, three-dimensional world onto a rectangular, flat piece of paper. The frontispiece from Historia mundi: or Mercator’s atlas ( STC 17824.5), 1635. They were also closely echoed in the frontispiece of Gerhard Mercator’s atlas. It remained largely unchanged throughout the approximately 30 editions that were published between 15. While it might have been a new, bold stand to represent four and a half continents on his title page, Ortelius’s personifications clearly seem to have struck a chord in the collective psyche of early modern readers. The last figure, our poor half-a-woman bust was there to represent “terra australis nondum cognita” as it is labeled on the world map that follows immediately after the preliminary pages in the atlas: we know there’s land to the south of everything else, but we don’t quite know what it is yet. While the name “America” had been floating around on maps since 1507, putting it on equal footing (so to speak) with Europe, Asia, and Africa was new. War-like, mysterious America, lounges at the bottom, holding a severed head, to show both barbarity and cannibalism. The two figures at the bottom would have been unfamiliar to Ortelius’s readers. They are, of course, the personifications of the continents.Įarly modern readers of Ortelius would have been immediately familiar with three of them: Europe, of course, sitting at a place of prominence at the top, with her crown and scepter and orb, showing the perceived European mastery of the world Asia, draped in rich silks and holding incense (note in the 1606 edition how the colorist has made Asia’s stomach area yellow…) and wild, dark-skinned Africa, crowned by the fiery sun. Readers are immediately confronted with four (well, really four and a half-we’ll get to the poor half in a minute) women in varying states of dress.

These hand-colored atlases are perpetual favorites when we do rare book show’n’tell sessions, and the intrigue starts right from the title page. Left, the title page from the 1595 Antwerp edition right, the title page from the 1606 London edition.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)